Physical Pursuits Help CMU Faculty Attain a Work-Life Balance that Matters

Media Inquiries

A holistic approach to health and wellness leads faculty members in the Carnegie Mellon University community to produce work that matters(opens in new window), including innovations in fields like artificial intelligence(opens in new window), the arts(opens in new window), humanities(opens in new window), neuroscience(opens in new window) and engineering(opens in new window). These campus leaders and mentors use athletic pursuit as ways to flex their muscles — and focus their minds.

Whether it’s on the water, in the dojo or on wheels, the journey toward health and well-being(opens in new window) is unique to each Tartan at CMU.

Roller derby grounds CFA’s cirCut Breaker

The trill of a referee’s whistle, clack of skates on the hardwood floor and shouts from teammates fill the air as Jenna Boyles(opens in new window), known as “cirCut Breaker” on the track, skates alongside members of Steel City Roller Derby at one recent practice at the Pittsburgh Indoor Sports Arena.

Boyles, digital and physical computing technician and adjunct professor of art for the College of Fine Arts(opens in new window), started skating with the team in 2022 shortly after joining the staff at Carnegie Mellon.

Her skater name references her day-to-day work with electronics at the university while still a nod to the sport itself.

“In my own art practice I do circuit bending, which is when you take apart old electronics and make weird instruments and do sound performances,” she said. “When you’re skating derby, you skate a circuit, it’s a closed loop, and you want to break through the pack.”

Her jersey number, 555, is another reference to electronics, the designation for a popular integrated circuit chip that has a variety of applications.

“I love analog electronics and it was one of the first chips I used when I first started learning,” she said, wearing a gold “555” charm on a necklace she came across while visiting New York City.

Starting off with Fisher-Price adjustable skates when she was young, Boyles remembered wanting to skate the fastest at friends’ birthday parties. Then, in high school, she became aware of roller derby as a sport.

“I was excited when I found out it was a sport, I just didn’t know at the time how to get into it,” she said, later considering getting started while earning her undergraduate degree in Baltimore and graduate degree in Chicago, but waiting until she had more stability with her CMU position.

“In this sport, you need good health insurance,” she said, adding that the team welcomes everyone regardless of skill level starting out. “When I came to practice for the first time, I had no idea. I didn’t know any of the rules or how much of a contact sport it is.”

Boyles began as a jammer, who wears a star on their helmet then skates fast through the pack to try to score points. In the last year, she has focused more on serving as a blocker, who tries to keep the jammer from scoring points, depending on the other skaters’ formations (called a “jam”) on the flat, oval-shaped track.

Each practice and bout (match) help clear her head and ground her, focusing on the present moment, she said.

“When you are in your head about anything and you have to do a sport, you have to pay attention to what's going on, and be aware of your body in a way that's helpful in getting you out of your head,” she said.

Go to section

- Jenna Boyles, College of Fine Arts

- Lee Branstetter, Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy

- Barbara Litt, Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences

- David Major, Tepper School of Business

- Tagbo Niepa, College of Engineering

- Tuomas Sandholm, School of Computer Science

- Barbara Shinn-Cunningham, Mellon College of Science

The life aquatic, and aerial, of a Heinz economics professor

A small octopus slinked up Lee Branstetter’s arm during a magical encounter under the water off the coast of La Jolla, California.

“It’s a privilege and a blessing just to interact with living things like that,” Branstetter said. “I find those experiences profound.”

Branstetter(opens in new window), the James M. Walton Professor of Economics and Public Policy at CMU’s Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy(opens in new window), grew up watching Jacques Cousteau documentaries on television and dreaming of becoming a marine biologist.

But he charted a different course. Branstetter joined Heinz College in 2006. He served on the staff of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, where he acted as the senior economist for international trade and investment.

His wife knew about his underwater aspirations. On a vacation in the Philippines in 2014, she surprised Branstetter and his son, who then was just old enough for a junior certification, with a scuba certification class.

“We learned in this tropical archipelago, which has some of the best scuba diving in the world,” Branstetter said. “From there, I was hooked.”

Since then, Branstetter has gone on to dive around the world. He’s received certifications for dry-suit diving and open-water diving. He’s made dives in east and southeast Asia, Israel, Latin America, Hawaii, Iceland, Florida and more.

“When you dive a coral reef, you see more wildlife in five minutes than you could see in five days hiking in a national park. It’s so dense,” Branstetter said. “I find it enjoyable, relaxing. It does not require a huge amount of raw strength. You want to save your air, by using measured movement underwater.”

In San Diego, fitting in a scuba dive, Branstetter became enthralled by paragliders soaring off the cliffs high above the surf.

“Isn’t that one of everyone’s earliest childhood fantasies?” Branstetter mused, “To be like a bird and lift up into the air?”

Since then, the economist — sometimes along with members of his entire family — has arranged a series of tandem flights with instructors in California, Hawaii and Taiwan.

He recalled once soaring above a state park near the edge of San Francisco.

“My pilot and I were riding the breeze, and a hundred yards to our left, a red-tailed hawk was hanging there, riding the same breeze,” he said. “In that moment, I felt like that bird.”

Teaching aikido brings Dietrich lecturer a steady calm

In the classroom at Carnegie Mellon, Barbara Litt teaches undergraduate students language and culture as a senior lecturer in Japanese Studies in the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences(opens in new window).

At Aikido Kokikai Pittsburgh in Regent Square, Litt shares a different side of Japanese culture, donning a hakama — a traditional Japanese garment — to guide students in the martial art of Aikido.

In both the classroom and the dojo, her students call her “sensei” as a sign of respect, acknowledging her many years of experience.

“It’s not a particularly lofty, exalted title — that comes more from my level as a sixth-degree black belt, and my service on my national federation’s board,” she said.

Litt first tried Aikido when friends invited her to see her future teacher, Sensei Shuji Maruyama, who was visiting from Japan. She was not necessarily seeking out a martial art or physical pastime specifically.

“When I stepped on the mat, I went, ‘wow, this is really fun,’ ” she said. “I never thought about doing it for 37 years. I just did it, now I wouldn’t dream of stopping, because it’s wonderful. I love that about traditional Japanese arts. It’s a lifelong practice.”

Aikido emphasizes deflecting attacks, instead of directly opposing an attacker with offensive force like striking or kicking.

“We evade the attack, we harmonize with it, and then we redirect it, usually into a throw. There’s a whole range of responses, but we never oppose an attack with force, we’re always blending and leading to take an attacker’s balance and move their mind,” Litt said.

In her CMU Japanese Studies(opens in new window) courses, she incorporates elements of Aikido when discussing traditional Japanese education and social structures. In one course she explores the role of martial arts.

“My favorite thing about teaching is the students who inspire me with their fresh thinking, especially the enthusiasm when they enjoy the course material and they bring something of themselves into it,” Litt said.

Aikido Kokikai, the specific style of the martial art that Litt teaches, uses four principles for coordinating mind and body: keep one point of focus, stay relaxed, use correct posture and develop your positive mind.

For example, Litt said she remembers noticing a change toward an optimistic attitude one morning when preparing to bike to Carnegie Mellon.

“I got on my bike to go to work and my inner talk said, ‘I get to go to work’ — normally, I would say, ‘I have to go to work’, or maybe ‘it’s time to go to work,’” she said, taken by surprise that she had shifted toward finding and radiating positivity.

“I love helping people find how to apply this to their lives,” she said. “I apply Aikido all the time in daily life without being attacked,” she said. “It’s kind of like jazz, you practice your chords and then you improvise.”

Tepper professor considers strategy on and off the tennis court

A chance mention of tennis started David Major(opens in new window) down a path to what he now considers the “best sport in the world.”

Major, who serves as associate dean for engagement and international partnerships and teaching professor of strategy for CMU’s Tepper School of Business(opens in new window), was aware of famous tennis players like Roger Federer, Pete Sampras, Jo-Wilfried Tsonga and Venus Williams, but he didn’t pick up a racket until his 40s.

When planning a trip with the help of a travel agent, Major took notice when she mentioned at the end of a conversation that she was headed to a “cardio tennis” class.

“I’m like, ‘What in the world? What’s this cardio tennis thing?’” he said. “Basically, you're running and trying to hit the ball as fast as you can, as hard as you can, and run to the next station. But it did get me on the court.”

Now, Major plays multiple times every week and has competed in singles and doubles league matches through the U.S. Tennis Association .

He recently won the regional title for the Midwestern States on his doubles team at the USTA National Championships (“It’s a trophy I’ll treasure for a lifetime!”), and placed third with his partner in a USTA doubles tournament in Wheeling. He was also named one of the New Pittsburgh Courier’s Men of Excellence(opens in new window) for 2025.

“I absolutely love it,” he said, explaining that he has pursued other athletic hobbies like training for and running a marathon, playing racquetball and, during college, rowing and biking. “Tennis still stands out, mostly because it is the one sport that I can do where I am completely focused on that experience on the here and now, that moment.”

Calculating not only where to move, but also how to reach the ball, allows Major to be present.

“It requires that even in those quiet times, or when you're not in the point, you've got to still be focused,” he said. “I love that, because I will forget everything else about work, life, you know, and it's this great freeing kind of moment.”

Major doesn’t go out of his way to incorporate tennis into his teaching or professional life, but said he occasionally mentions it in conversation with CMU colleagues.

“I'm a strategy professor, and so strategy is hugely important with tennis, not just what you’ve got to do at that moment, but how all that fits the larger picture,” he said.

Previously, Major was a board member of the National Junior Tennis League, and, this summer, he joined the Highland Park Tennis Club, to get more involved with programs like the club’s blind and low vision tennis clinics(opens in new window).

“A big part of my work around engagement here at CMU is trying to find ways to make sure that as an organization, this is a place available to all, and this program is a key example,” he said. “The community connection is huge to me.”

‘Ahoy!’ Engineering professor gets Ph.D. students out of the lab and in to kayaks

Tagbo Niepa(opens in new window), the Arthur Hamerschlag Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering and Biomedical Engineering in the College of Engineering(opens in new window), led a group of seven students who paddled through Raccoon Creek State Park about an hour’s drive west of Pittsburgh one late afternoon.

Kayaking since he moved to the Pittsburgh region about eight years ago, Niepa has organized three trips with students.

“We enjoy spending time together,” he said, adding that he organizes events outside the lab about once every month, including two racquetball tournaments.

Niepa also stays active as a scuba diver(opens in new window) and recently returned from a diving trip to Belize. He said he believes that no matter how near or far someone travels, faculty members and students should prioritize a healthy work-life balance(opens in new window).

“When I’m in Pittsburgh, I’m on campus every day, including on the weekend,” he said. “But I also make time for myself to be able to enjoy the outdoors, like walking on a trail or biking and kayaking, or going far away for scuba diving. It is so important for our mental health that we do that. We have to be much more active and find a way to enjoy ourselves.”

Out on the water, the group paddled toward a marshy spot where a great blue heron waded along tall plants, then caught a fish in its beak.

“It’s quiet and peaceful, which we don’t get a lot of at school,” said Hannah Gedde, a chemical engineering Ph.D student, back on the shore. “It helps all of us to connect with each other.”

Sailboat racing tactics serve as game theory for SCS professor

The waves and wind on a pleasant May afternoon were calm enough that Tuomas Sandholm(opens in new window), and his daughter Annika, 17, could launch their sailboat.

But that changed once they and other members of the Moraine Sailing Club were about to start their race. Waves and gusts on the water were so great that all of the boats’ sails were whipping against their masts. One boat capsized briefly.

“It was exciting, we had a lot of wind,” Sandholm said after coming back in to shore after the race was called off. “We just got a little bit of practicing in.”

Sandholm, the Angel Jordan University Professor in the School of Computer Science(opens in new window), started sailing with his parents when he was 2 years old, growing up in Finland, where they spent weeks on a sailboat every summer.

Before joining Carnegie Mellon, he was a champion windsurfer, winning the Finnish championship, finishing fifth in European Championships, and achieving 12th in the World Championships. Now, his nautical pastime of choice includes sailing in races an hour north of campus.

“It’s a really nice community, a lot of good friends, and it’s also a fairly competitive fleet, which makes it more fun for racing,” he said. “We’ve been developing it, so it’s more competitive now than it used to be 15 years ago.”

Sandholm said he enjoys being out on the lake, compared to the ocean waters.

“There are no sharks in the water here, so that's great if you fall in,” he said. “You don't get salt in your stuff, and you don't have to wash it afterwards. It's a very easy place to sail, very safe.”

Sandholm said he doesn’t often talk about sailing with his colleagues, joking that all the details may not be relatable.

“If you’re a sailor, it’s fun to talk about, but if you’re not a sailor, it’s not that fun to listen,” he said, laughing.

However, sailing can serve as an example of his research in artificial intelligence that explores game theory. In 2023, he earned the AAAI Award for Artificial Intelligence for the Benefit of Humanity(opens in new window).

“In game theory, the best way for you to strategize depends on how the others play and vice versa,” Sandholm said. “Sailing is a very tactical sport, especially this kind of sailing where everybody has the same boats and same sails, so it’s all about the skill, and a big part of the skill is reading the wind and placing your boat with respect to other boats in a favorable way.”

Sailing requires a certain degree of physical strength, but more so needs mental acuity, including focus on the wind and continuous adaptation to it, he said.

“When the wind is light, it really is a patience game, and you have to stay fully focused all the time. That is difficult to do if you haven’t practiced a lot because you have to stay focused for many hours in a row and it feels like nothing is happening,” Sandholm said. “And it’s important not to lose focus in heavy air like today because otherwise bad things can happen quickly.”

Even the best racers get lucky or unlucky sometimes — what Sandholm called “stochasticity,” used to describe uncertainty.

“That makes it very interesting because not everybody has to be an equally good racer, and they can still be challenging opponents in some races,” he said.

Sandholm said his philosophy on the water is simple: “Having fun and staying calm … trying to improve all the time, every race, every year.”

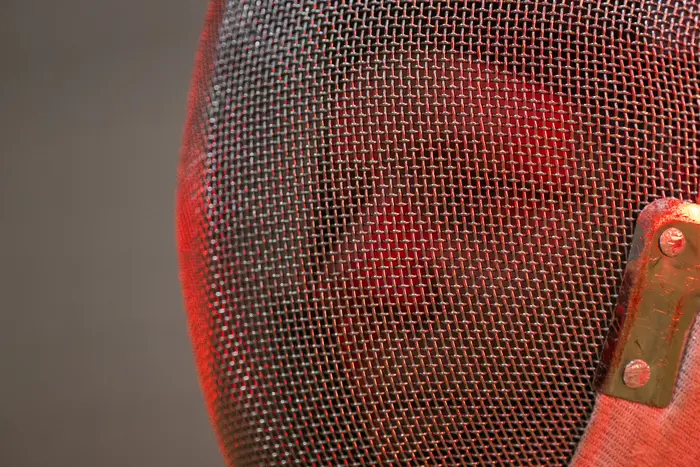

MCS dean uses ‘devious’ thinking in saber fencing

Fencing requires quick-thinking strategy mixed with physicality and bodily awareness, which is why Barbara Shinn-Cunningham(opens in new window), the Glen de Vries Dean of the Mellon College of Science and professor of neuroscience, enjoys the sport so much.

“It’s the perfect sport for CMU,” she said, one evening practicing alongside members of the university’s fencing club(opens in new window). “It’s really intellectual, but you can challenge yourself.”

When one of her sons was in high school, Shinn-Cunningham learned saber fencing alongside him in Boston.

In the 12 years since then, she has competed in national tournaments, including as a member of Team USA for the 2019 Veteran Fencing World Championships in Egypt, where she earned a bronze medal.

Compared to her academic endeavors, Shinn-Cunningham said the improvisational mental agility of the sport appeals to her, much like playing a musical instrument.

“I’m still getting better as a fencer because it’s so much about technique,” she said. “It’s about reading the other person.”

The three major categories of fencing, all with slightly different technique, target areas and scoring, are divided by the weapon used: foil, épée, or saber. A foil is lightweight whereas an épée is heavier and larger, but both score hits using only the tip. With saber, the entire edge of the sword awards points.

“Saber, which is so fast-paced, appeals to me,” Shinn-Cunningham said. “It forces me to try to be in a moment because most of the time my mind is in seven different places at once simultaneously.”

Shinn-Cunningham said that outside the CMU club, Pittsburgh fencers are more likely to compete with foils, encouraging her to try it. But she still prefers saber.

“For a long time, I was the highest-ranked saberist in western Pennsylvania, because there were five of us,” she said.

Fencers often compare the sport to the game rock-paper-scissors, where players have to make offensive and defensive decisions quickly.

“As long as I am patient and read him correctly, or draw him into going somewhere where I know where he's going to go, so I can get his blade, it’s my point,” Shinn-Cunningham said. “So it’s like this mental game against your opponent constantly.”

Other types of physical fitness end up feeling like a chore, where she said she had to convince herself, for example, that she can binge a Netflix show while she rides an elliptical machine.

“This is a way for me to exercise that is so much fun I look forward to it,” Shinn-Cunningham said, who practices alongside students in the CMU Fencing Club, who seem to enjoy her being there as much as she does.

“They see that being clever, being smart and being devious is as important as being athletic,” she said.

The club often offers fencing opportunities on the Cut(opens in new window) each academic year.

“More people should do saber at CMU because then there would be more people to fence with and more fun,” Shinn-Cunningham said. “They can come beat up on the dean.”