Play Us a Song, 𝝅-ano Man

Media Inquiries

How does a piece of pi sound?

Inside Carnegie Mellon University’s Vlahakis Recording Studio(opens in new window), Evan O’Dorney plays a peaceful, thoughtful melody on a Steinway B piano. Embellished notes stick out, a code containing the first 97 digits a fundamental constant in mathematics — pi.

“I’ve always had an interest in memorizing numbers. To memorize longer strings of numbers, I found it useful to turn them into a melody,” he said.

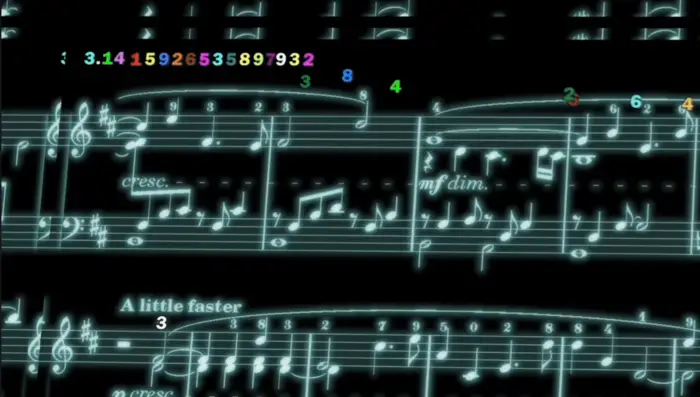

Using the eight notes contained in scale of D major, and one additional note above and below, O’Dorney, a postdoctoral researcher in Carnegie Mellon University’s Department of Mathematics(opens in new window), assigned each digit 0-9 to a note to create the melody. By memorizing the melody, he had, in turn, memorized the digits of pi.

At Carnegie Mellon, his research is in the realm of number theory. He is working on quintic equations, but his love of numbers started early. O’Dorney recalls checking out counting videos from his local library at age 2. His mother used addition and subtraction flashcards to teach him arithmetic.

“I’m drawn by the beauty of mathematics. When you write a theorem, you’re expressing a thought that’s always been true from all eternity. It has just remained for us to discover that it’s there,” O’Dorney said. “When I’m doing research, it’s like I’m finding a path up a mountain, one that I did not build but chose to scale. There are some paths that go nowhere, and some that go somewhere. And it’s all a wonderful journey.”

In music, O’Dorney has the same goal: to discover something beautiful, and write it down.

“When I need a break from mathematics, I’ll often turn to music,” he said. “I grew up with music. My mom has sung in many choirs. She can sing the harmony to any song by ear. When I was 4, going on 5, she taught me the basics of the piano, and I never stopped.”

A recording collaboration born at Carnegie Mellon

In Riccardo Schulz(opens in new window)’s Multitrack Recording class, students arrange microphones to record artists from CMU, Pittsburgh and beyond. Students in the class arrive with varying degrees of experience. Some have prior knowledge, while others are totally new to digital audio workstations and recording. The class collaborated with O’Dorney to record the pi composition, which he wrote in 2016.

Schulz said musicians at Carnegie Mellon can come from any discipline.

“We had a student come in yesterday for a project. He sits down to check out our piano, and he’s playing a Franz Liszt transcription of a Bellini opera, which is almost impossible for any musician to play — he’s rattling off this thing as if it’s nothing. And he’s interested in neuroscience(opens in new window).”

Schulz, a teaching professor of sound recording and director of recording activities in the School of Music(opens in new window), was already familiar with O’Dorney’s mastery of memorization. He had seen it when O’Dorney won the 2007 Scripps National Spelling Bee(opens in new window).

How to end the never-ending (Happy 𝝅 day)

The final dilemma: where to end a song relating to a number that never stops and never repeats.

“My first question was, why only 97 digits? Why not go three more to 100?” Schulz said.

O’Dorney said he stopped when he found a natural conclusion.

“The digits leading up to the 97th are 2, 5, 3, 4, 2, 1, 1. And in our scale system, 1 is the tonic. It’s the note of rest, and pi bounces infinitely often among the notes.”

Pi day is celebrated annually on March 14 (3.14). O’Dorney reflected upon its significance.

“Pi is one of the most important numbers in mathematics. And it’s a strange thing to look at. For example, look at the six 9s in pi,” O’Dorney said, referring to a section that begins in pi’s 762nd decimal place known as the Feynman point. “Statistically, you should have to go out at least 100,000 digits to get six of the same number in a row. But those 9s occur really early. It’s mysterious. It gives me pause. And it puts me on guard against interpreting things that happen in life as coincidence.”

The first 97 digits of 𝝅

3.141592653589793238462643383279502884197169399375105820974944592307816406286 20899862803482534211