NEH Fellowship Supports Dworkin's Project on Cuban Immigrant Theater

Media Inquiries

Twenty-five years ago, Kenya Dworkin(opens in new window) took a walking tour of Ybor City(opens in new window) in Tampa, Florida, and discovered the project that would set the stage for her research for decades to come.

In the mid-19th century and beyond, Cuban immigrants and exiles began to leave the island and settle in Tampa, bringing with them many traditions. Like other ethnic groups at the time, the Cubans banded together and formed mutual aid societies and clubs — buildings that served a myriad of purposes such as providing healthcare. They always housed large theaters.

Touring one such building, Dworkin, an associate professor of Hispanic studies(opens in new window) and translation at Carnegie Mellon University, made it her mission to track down, collect and preserve the plays written and performed in these theaters. And with a recent $60,000 fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Dworkin will finish her book examining how the plays' content reveal the cultural heritage of the Cuban community and the Americanization that occurred for the group over time in Tampa.

"My project is a mirror, not just up to these immigrants, but up to the society they came to," Dworkin said. "I don't think that we've gotten to the point where we can stop studying immigration, because this continues to be a country of immigrants."

The Cubans that came to Tampa brought their primary industry: cigars. Cigar factory workers auditioned and paid readers to come to the factory floor for hours a day to read newspapers and books, translating them on-the-fly from English to Spanish. Before the internet, television and radio, these readers broke the tedium of the repetitious work and kept the workers informed on the issues of the day.

Kenya Dworkin reads a story at the

�Carnegie Museum of Art's Story Saturdays in 2021.

Actors Salvador Toledo and Chela Martinez performed plays at the Circulo Cubano (Cuban Club) Theater.

The club theaters were a popular form of entertainment and social commentary.

At night, community members would file into the theater to watch plays dealing with topical subjects like war, the expectation of workers, wanting to return home, mixed marriage and more.

"Hearing these stories, a lightbulb went off," said Dworkin, who was born in Cuba and immigrated to the U.S. as an infant. "These plays really resonated with me. I can identify with their life stories and where they came from."

Dworkin began seeking the scripts and videotaping oral interviews with senior community members who could give first-hand recollections of the theaters. In 25 years, she amassed 55 plays, none of which have ever been published. Hundreds more are likely lost to history, she said.

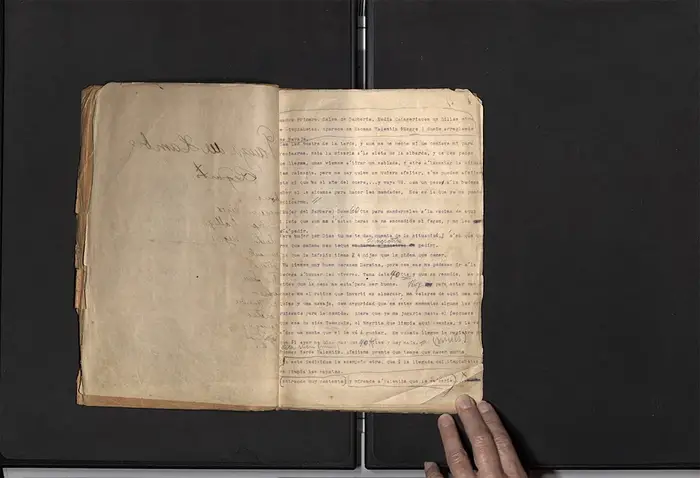

Fragment of play found at Unión Martí-Maceo (Black Cuban Club) titled "La danza del hambre" or "The Dance of Hunger."

"Through the decades, the plays that were written locally begin to reveal the incipient Americanization of this community. Through the '30s and World War II, they created a mixed identity that was Cuban, and Spanish and somewhat American. One of the things that also caught my eye about this genre is it's very problematic because it's blackface theater."

According to Dworkin, examining the use of blackface and its contextual relevancy became clear and necessary to her during the summer following the death of George Floyd.

"They survived so much adversity and still had a joy for life, even with all their flaws," Dworkin said. "My goal is to look at these plays through the lens of what it says about society, not so much as an artistic form.

"There are important lessons to be learned from these people developed in a microcosm who were surrounded by an extremely racist society, and thrived, even though, as much of this theater reveals, at the expense of their darker-skinned co-nationals/compatriots, a reality that echoes with our own history and reality in this country."