Better Screening Tool for Sickle Cell Disease Progression

Media Inquiries

Carnegie Mellon University and University of Pittsburgh researchers have shown that a simple, noninvasive light-based technology could help doctors better track how sickle cell disease affects the brain as patients age. The technology is known as near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) and can measure blood and oxygen changes in tiny vessels, which could lead to earlier detection of complications and provide a new tool for improving care in regions where the disease is most common.

As people with sickle cell disease age, they can develop problems with small blood vessels in the brain, leading to reduced blood flow and difficulties with thinking, memory and other functions. The disease changes how oxygen moves through the body, but its effects on the brain haven’t been well-studied.

One warning sign in people with sickle cell disease is trouble with cerebral autoregulation, the brain’s ability to keep blood flowing steadily even when blood pressure changes. Right now, doctors mostly check this by looking at blood pressure and blood flow in the body’s larger vessels, using tools like an arm cuff or ultrasound. But these methods, and in particular ultrasound measurements, don’t work well in adults and can’t show how much oxygen is reaching the brain. Measuring what’s happening in the brain’s smallest vessels — where these problems often begin — has been especially difficult, and often complications aren't detected until after the damage has occurred.

NIRS could be an important screening tool for cerebral small vessel disease in adults with sickle cell disease.

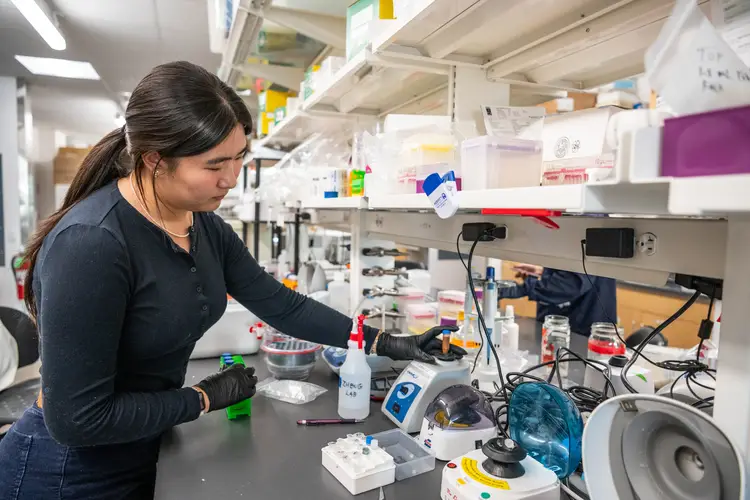

“Rather than looking only at the larger vessels in adults, our study focused on the hemodynamics associated with blood pressure changes in the smaller vessels, and what NIRS can reliably detect about blood and oxygen changes there,” noted Sossena Wood(opens in new window), assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Carnegie Mellon. “Unlike prior studies done on large vessel abnormalities or at rest, this one measured dynamic cerebral autoregulation and participants’ response during breathing, taking things a step further toward positive utility.”

This research has also been foundational for work Wood’s group(opens in new window) is doing abroad, in partnership with Carnegie Mellon University in Africa(opens in new window) and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Adult Sickle Cell Program.

In Nigeria, they are participating in a clinical trial with colleagues from Pitt and Lagos University Teaching Hospital, where sickle cell disease patients are given an affordable medication, erythropoietin, that boosts hemoglobin levels. NIRS allows the researchers to track blood and oxygen changes in tiny vessels, finding that the medication led to higher oxygen levels in patients after each dosage.

“The whole motivation is to show that NIRS is reliable and could do more than it’s currently utilized for,” said Wood. “The sickle cell disease population is very young, and they’re getting older because of the therapies that are helping them live longer. As they age, there is a lot we are learning about the pathology of the disease and NIRS is a useful point of care screening tool in environments where sickle cell disease is most prevalent. I’m excited to be part of improving measurement tools for sickle cell disease progression and in turn, quality of life for those living with the disease.”

This research was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health and the University of Pittsburgh’s CTSI Research Across the Lifespan pilot program. Carnegie Mellon faculty member Jana Kainerstorfer(opens in new window) was an additional collaborator.