Women in Science Highlight Mentorship, Outreach as Integral to Career Success

Media Inquiries

The road that makes up a career, especially one related to academics and research, is built one brick at a time.

Those individual bricks come from every opportunity someone takes, said Rebecca Nugent(opens in new window), the Stephen E. and Joyce Fienberg Professor of Statistics & Data Science at Carnegie Mellon University.

“All the major advances that come with people making huge leaps in their careers, they all started with putting down little bricks, one at a time,” she said. “Eventually, those bricks become something really big.”

No matter the discipline, mentorship and outreach are important to encourage scaffolding opportunities that might start with agreeing to meet for coffee, turning in an application or asking for feedback.

“I’m a big believer in building roads brick by brick,” she said. “I have been the beneficiary of many people believing that I could take that next step, and I think that approach is crucial for us developing the next generation of scientists and educators.”

Just one in three scientists worldwide is a woman, according to a report released in 2024 by UNESCO(opens in new window). At Carnegie Mellon, women in the sciences contribute to advancement and innovations at the forefront of discovery, while lifting each other along the way.

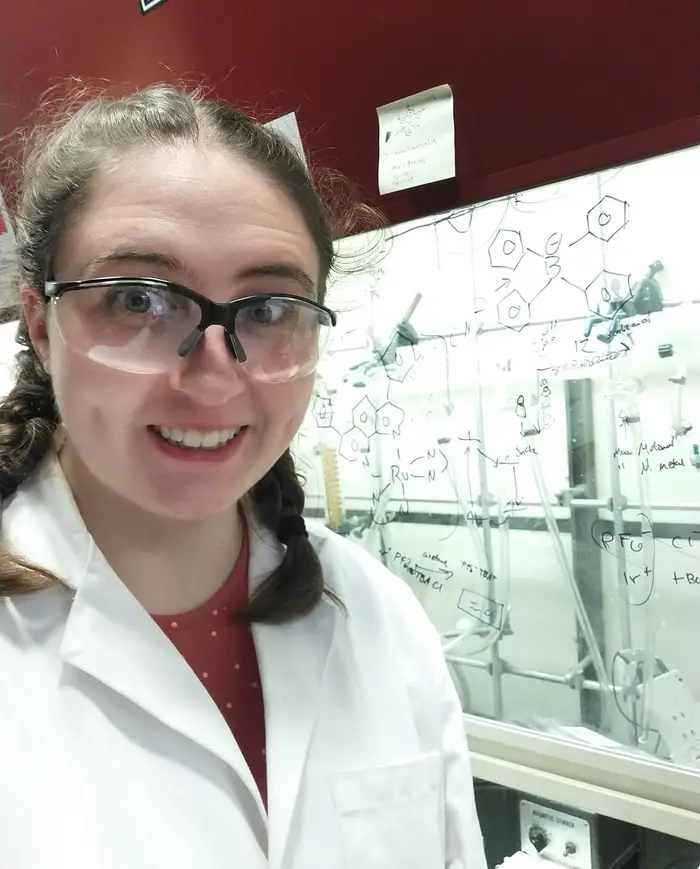

Sydney Prescott

When she was in high school, Sydney Prescott found out about the Department of Chemistry(opens in new window)’s annual student-produced murder-mystery musical dinner.

“This program showed that people cared so much that they were willing to do something so elaborate for fun,” she said. “I realized this would be a good place for me.”

Now a senior majoring in chemistry(opens in new window) and environmental & sustainability studies(opens in new window), Prescott has been working with about 15 other students to produce this year’s dinner, which is themed to the musical “Chicago,” set for March 19.

The production, a CMU tradition for almost 20 years(opens in new window), provides a bonding experience for those involved and a way for them to share their skills outside of the classroom.

“I’ve really enjoyed working on different teams, no matter what the activity or opportunity has been,” she said. “For something like the murder-mystery dinner, I’ve seen how everyone has to come together and figure out each other’s strengths to work toward the end goal of the final performance.”

Prescott has worked for three years as an undergraduate researcher in the lab of Chemistry Professor Stefan Bernhard(opens in new window). Prescott synthesizes iridium-centered complexes and tests their luminescent properties and their potential applications in renewable energy systems.

“I’ve had to adjust the synthetic method to improve the yield and purity,” she said. “It’s been a lot of work on the bench, doing chemistry.”

She credits Karen Stump(opens in new window), teaching professor and director of undergraduate programs in the Department of Chemistry, with helping her find opportunities. Aided by chemistry doctoral student Mitch Baumer, she learned how to contribute to the lab’s research and completed a project funded by the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship(opens in new window).

Prescott has applied to doctoral programs to study inorganic chemistry and renewable energy.

“I feel a lot more prepared for the next step. I want to be able to have leadership over the experiments I’m running,” she said. “Whatever my future goal is, I want to have a really solid understanding of research and be able to make informed decisions about what direction the project goes in.”

With the Women in Science club(opens in new window), Prescott has helped plan activities such as partnering with a local Pittsburgh Girl Scout troop to teach a science badge. She served as president of the student group last year and as vice president the year before.

“Leading that group has helped me meet other women in science and organize outreach activities in the community,” she said. “I definitely didn’t know any college students in science when I was little, so we give them the experience of getting to see what students at Carnegie Mellon are really like."

She served as a residential assistant her first two years and now, as a community adviser, oversees a team of RAs.

With her involvement in student life, Prescott said she has learned how working together toward a goal — whether a project or a science-infused musical — helps build connections with other students more easily that can grow in to an authentic network in the future.

“Even casual social events make it easier to meet people, then you have a support system that helps you succeed,” she said.

In high school in Victor, New York, she liked to keep busy with extracurricular activities, including earning her Girl Scout Gold Award, which combines leadership and community service.

Continuing to take part in community-building during her college career at Carnegie Mellon felt like a natural progression.

“I’m a big believer that the more effort you put into an experience, the more you’ll get out of it,” Prescott said.

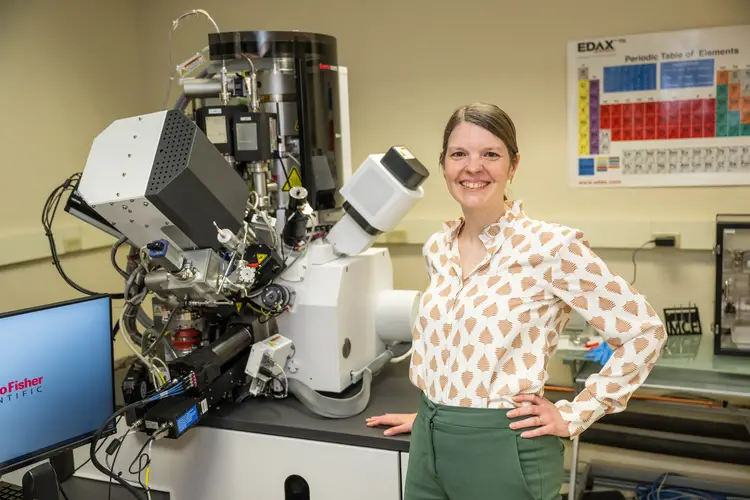

Valentina Dutta

The construction of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the particle accelerator at the European Organization for Nuclear Research, known as CERN, in Switzerland, captured the interest of Valentina Dutta(opens in new window) when she was a teenager in India. She read a story about its construction in the science section of her local newspaper.

“I found it really fascinating, you know, with this big collaboration that was composed of scientists from all around the world working together to build something, to discover something fundamentally new about the universe,” said Dutta, now an assistant professor in the Department of Physics(opens in new window) within CMU’s Mellon College of Science(opens in new window).

As an undergraduate researcher, she worked at Fermilab near Chicago on another particle accelerator, the Tevatron, which similarly uses electromagnetic fields to propel charged particles at very high speeds and measure the energy and reactions when they smash together.

Years later, Dutta, as a doctoral student, worked in Switzerland on the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment at the LHC. She was in the room when the discovery of the Higgs boson particle(opens in new window) was announced to the world in 2012.

“The article I’d read when I was young had talked about this quest to discover the Higgs boson, which was the last missing piece of the standard model of particle physics,” Dutta said. “I was so fortunate as to actually end up working on that.”

A breakthrough in scientific understanding of the structure of the universe and how particles acquire mass, the subatomic particle relates to Dutta’s work today.

“You look for the particles you know it decays into and try to match it up with what you expect for the Higgs itself,” she said. “I was looking for evidence of its decays into a particular type of particle called the tau lepton.”

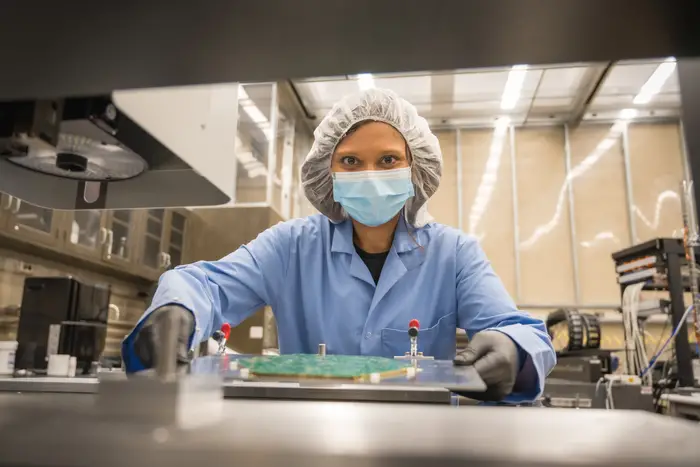

Now, as part of a major collaboration across the world, Dutta and other Carnegie Mellon faculty members are leading an effort here to build and test modules(opens in new window) that will be used in the study of particle physics.

In the ongoing CMS experiment, detectors capture 3D images of the particles’ impacts at the rate of one every 25 nanoseconds, or 40 million images a second.

Dutta, along with Professor Manfred Paulini(opens in new window) and Associate Professor John Alison(opens in new window), are leading a team building 20-centimeter hexagonal electronics modules at Carnegie Mellon's module assembly center for a High-Granularity Calorimeter upgrade to the CMS detectors. The upgrade will enhance the quality of the recorded data as well as cope with large amounts of ionizing radiation.

Over the next three years, the teams at Carnegie Mellon hope to build 5,000 modules.

“We’re in the pre-production phase now and will be producing up to 12 modules per day in a few months’ time,” Dutta said.

Looking back, Dutta remembers the importance her undergraduate research mentor, the late Meenakshi Narain at Boston University, had on her, and she keeps mentorship at top of mind when working on such a large-scale, worldwide collaboration.

“I’ve definitely been fortunate to find mentors along the way who helped me gain perspective as role models,” Dutta said. “I try to pass that on in my relationships with students and collaborators because mentorship is hugely important.”

Coty Gonzalez

As a research professor at the Department of Social and Decision Sciences(opens in new window), Cleotilde (Coty) Gonzalez examines how humans make choices in dynamic environments.

Then, those thought processes are used to create and train computer models.

Once the computer models are perfected, they can, in turn, be used to help humans make even better decisions.

“Our main tool for doing that is a computational cognitive model,” she said. “These computer programs emulate human cognitive processes from perception to action. Then we can use that tool, that computational model, to help humans make better choices.”

Gonzalez founded the Dynamic Decision Making Laboratory(opens in new window) in 2002, after joining the faculty at Carnegie Mellon in 2000.

“My interest in decision-making came from very early on, but was more about the computer, not so much about the human,” she said. “But during my Ph.D., I realized there needs to be a cohesion between the human and the computer for decisions to be made properly.”

She has been principal or co-investigator on a wide range of multimillion and multiyear collaborative efforts with government and industry, including NSF AI National Institutes, Multi-University Research Initiative grants from the Army Research Laboratories and Army Research Office; large collaborative projects with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA).

As research co-director of the National AI Institute for Societal Decision Making(opens in new window), Gonzalez helps lead a $20-million, five-year program that examines interdisciplinary solutions to aid in disaster management and public health.

When a disaster happens, which is usually sudden and evolves in a nonlinear way, researchers are studying human reactions that can better allocate resources.

Creating tools for future research using data from human decisions also fuels the institute’s work, Gonzalez said.

“I’m looking forward to advancing our work on AI,” she said. “There are so many ways to bring my cognitive models and demonstrate the benefit for AI and machine learning in particular.”

The team, including four undergraduate students from different departments, is developing a prototype game that uses the data as part of one of those tools for disaster managers.

Data will inform and be synthesized into a large-language model, which the manager could use to decide where to send resources and of what types.

“I believe in the human ability to adapt to dynamic tasks. That is indeed a trademark of the kind of work we do,” Gonzalez said. “We study learning and adaptation, so how do humans build adaptation? We build it through a diversity of knowledge, experiences and cultural backgrounds.”

Using instance-based learning theory, which she developed along with other researchers in 2003, models for cybersecurity, network science and human-machine teaming have emerged.

“Usually, decision-making is studied by assuming people evaluate all their possible options and weigh the pros and cons,” she said. “However, most people actually use their experience or someone else’s experience to make decisions.”

The theory has evolved, but the complexity and basic building blocks of human memory that we use for decision-making are the same, she said.

“I still believe the way to address challenges the real-world presents to us is to study complex tasks, not simplistic ones,” she said.

During her more than 20 years leading the lab, she has mentored 36 postdoctoral researchers — and most have added a pin to a world map in the SDS office.

“It’s important to me that they are productive and feel motivated,” she said. “Some of them might think I’m pretty tough, but I want them to be productive, while recognizing their abilities and interests.”

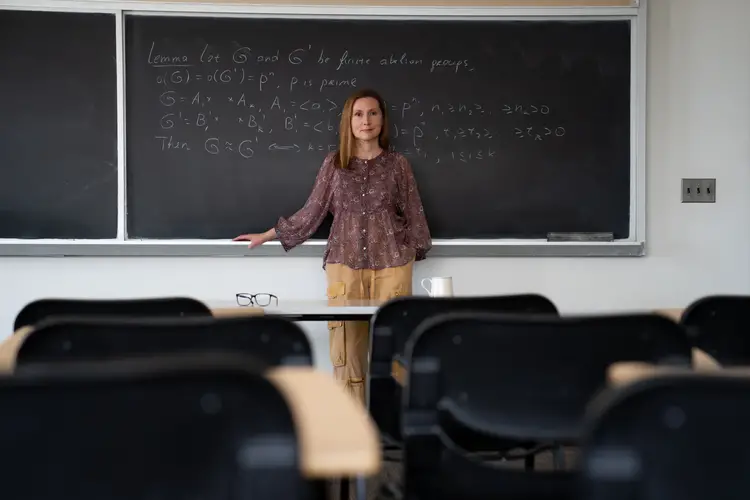

Rebecca Nugent

When Rebecca Nugent began her career in academia, she considered how to teach college students about data, but now more than ever, she believes the everyday person should also know more about data and how it affects them.

“If we don't empower people to learn about data and to use data to make informed decisions in their own lives, then it's a huge missed opportunity for us,” she said.

Nugent serves as the department head for the Carnegie Mellon Statistics & Data Science Department(opens in new window) in the Dietrich College of Humanities & Social Sciences(opens in new window).

Her current research focus is the development and deployment of low-barrier data analysis platforms that allow for adaptive instruction and the study of data science as a science.

With an increased amount and access to data, especially thanks to artificial intelligence, the foundational framework for interactions with technology is changing.

“How do we be responsible about this?” she asked. “How do we use AI and data science to help people?”

Statistical principles such as randomness, uncertainty and what it means to be a prediction versus a fact should be a part of any future data literacy programs, apps or projects, Nugent said.

“What can we do with developing technology to provide more personalized support or personalized treatment to help people make decisions about their own health care journey,” she said. “Imagine if that information is wrong, or imagine if they don’t know how to interpret the information that they’re getting.”

As she serves as education and outreach lead for the National AI Institute for Societal Decision Making(opens in new window) (as part of the leadership team with Gonzalez), she keeps these principles in mind as well.

“If people are uncomfortable with data-centric technology and nobody understands what its purpose is, how can it help?” she said.

She also is a part of the Carnegie Mellon Sports Analytics Center(opens in new window) that uses sports data as an entry point to encourage interest in how to better understand data, and works with the SCORE Network(opens in new window). Funded by the National Science Foundation, the national network is dedicated to creating and sharing Sports Content for Outreach, Research and Education in statistics and data science.

“We're creating modules that explain data science and statistics content to people who are newer to these fields, but we do it with sports analytics,” Nugent said.

Data and artificial intelligence isn’t meant for a vacuum. It’s meant for people.

“People are central to everything that we're doing,” Nugent said. “Anything that we're designing and building, we're doing with the idea that it's either going to be used by a person, or it's going to help support someone.”

With every research project and collaboration that she works on, Nugent said she prioritizes mentorship and advocacy.

“Those aren’t the same thing,” she said. “Mentorship is important for answering people’s questions, making sure they have information, then providing them with support to move forward. Advocacy is providing opportunities for talented people to grow and rise to the occasion.”

For Women's History Month, Carnegie Mellon is featuring the work of women across the science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields.