HIV Protein Switch May Help Virus Squeeze into Host Cell Nucleus

Simulations on Bridges-2 help visualize rare, transient shape change in capsid protein

Media Inquiries

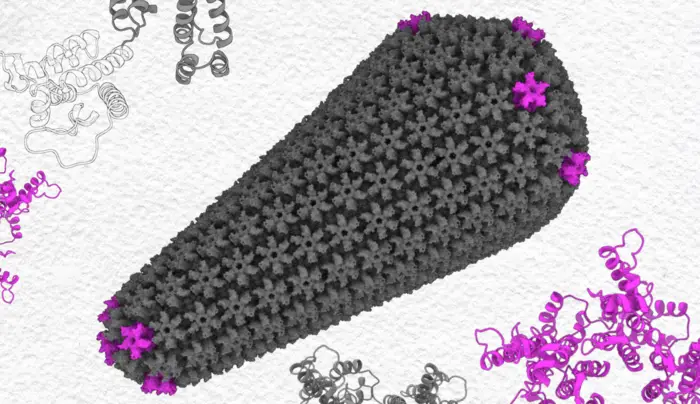

A crucial stage in HIV infection, the virus that causes AIDS, is insertion of the viral capsid — the inner protein coat containing its genetic material — through the host cell’s nuclear pore.

The mechanism by which the virus achieves this feat — squeezing a large structure through a small entrance, is a puzzle. It’s also a potential target for better therapies.

At the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center(opens in new window), a joint center of Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh, simulations on the flagship Bridges-2 system by a Pitt team revealed how changes in the shape of the HIV-1 capsid protein may help the capsid be more flexible. The method may also be useful for studying flexibility in other important proteins.

An unusual puzzle

Modern antiviral therapies have turned HIV into a chronic, but survivable, disease. Death rates are at a 20-year low.

On the other hand, doctors are unlikely to meet their goal of eliminating AIDS as a health threat worldwide by 2030. In some populations, HIV infection is increasing, and a vaccine does not exist. That’s why scientists studying AIDS continue to search for weak spots in the virus’ infection cycle.

HIV inserts its genes into the host cell’s nucleus in an unusual way. It doesn’t import its RNA genetic material piecemeal. Instead, it stuffs its whole wedge-shaped capsid — basically the whole virus minus its outer membrane — through the nuclear pore in one piece.

The HIV-1 capsid protein makes up most of the protein mesh that forms the capsid. It does this by making connections between separate capsid proteins at different scales. First, either six or five copies of the protein link together via their N-terminal domains to form six-sided hexamers or five-sided pentamers. Then, the opposite end of the protein, the C-terminal domain (CTD), links with CTDs of neighboring hexamers or pentamers to connect them and form a mesh that surrounds the genetic material. The wedge of the capsid is kind of like a soccer ball, which also needs hexagons and pentagons to make a curved shape.

The CTD connections between two proteins — called dimers — in neighboring hexamers or pentamers can adopt different shapes that change the angles between those shapes. Before assembling into the capsid, about 85% of the CTDs connect in the D1 shape; the rest, the D2 shape.

Scientists suspected that the pointy end of the capsid’s wedge might help it squeeze through the nuclear pore. What they didn’t know was whether the ability of the CTD to shift angles between the hexamers and pentamers might play an additional role in making the capsid more flexible, and better able to deform to push through. One problem was that the D1 to D2 conversion is so fast, and the D2 shape is so outnumbered by D1. Because of this, D2 doesn’t show up well in imaging and is hard to simulate. D2 was basically invisible to both methods.

Darian T. Yang, now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Copenhagen, wanted to know what D2 looks like, and whether the capsid protein’s ability to change shape might give the capsid extra flexibility to squeeze through. Then working as a graduate student with both Professor of Chemistry Lillian T. Chong and UPMC Rosalind Franklin Chair of Structural Biology Angela M. Gronenborn at Pitt, he carried out an exhaustive series of simulations of the capsid protein with PSC’s National Science Foundation-funded Bridges-2 supercomputer(opens in new window). He got computing time on Bridges-2 via an allocation from ACCESS, the NSF’s high-performance computing network, in which PSC is a leading member.

GPU Power Aids Research

The simulations needed powerful graphics processing units (GPUs), and plenty of them. Yang’s simulations would require many repetitions to work out the different ways in which the proteins can behave. Bridges-2, with 34 GPU nodes containing a total of 280 late-model GPUs, fit the bill. For comparison, a high-end graphic design laptop typically has two GPUs.

“It was really nice when Bridges-2 came out … It was a big shift in the amount of speed that we could get with our simulations,” Yang said.

The team compared its simulation results with laboratory experiments using an imaging technology called nuclear magnetic resonance, or NMR, which can track the shape of the protein via a fluorine atom that scientists attached to the natural protein. By going back and forth between real-life results and the behavior of the virtual proteins in the computer, they could be more confident the simulations were capturing reality.

The simulations, which were the first of their kind, produced switching rates and populations of the D1 and D2 shapes that matched the behavior of the capsid in the lab experiments. The team announced their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in February 2025(opens in new window). The results are encouraging, suggesting that simulations can pair with experiments to find new targets for HIV drugs or vaccines.