Iris Lunar Dream Capsule Will Head to Moon on Next Astrobotic Lander

Media Inquiries

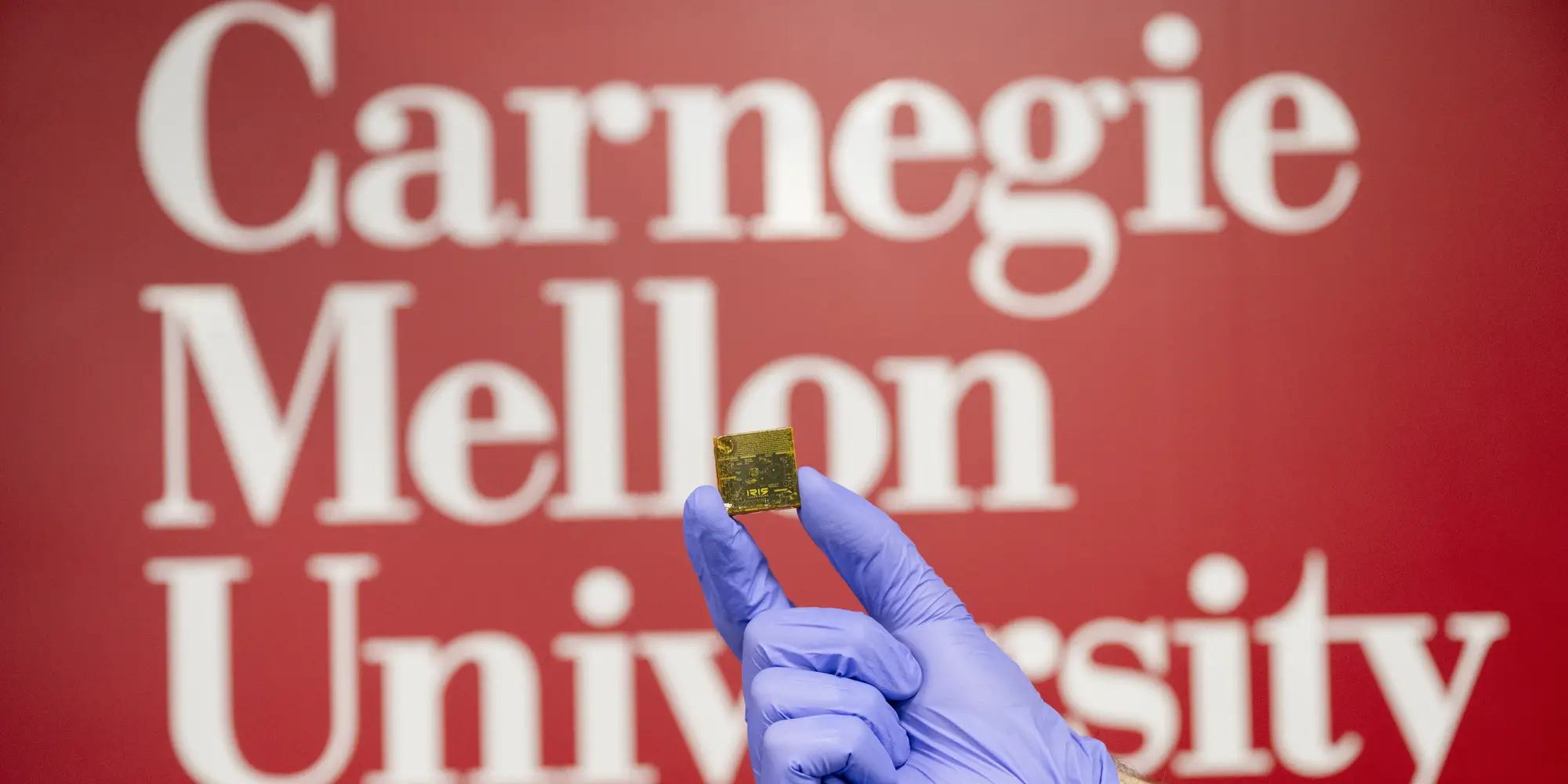

Iris — the lunar rover built by 300 students across Carnegie Mellon University’s seven colleges — will head back to the moon.

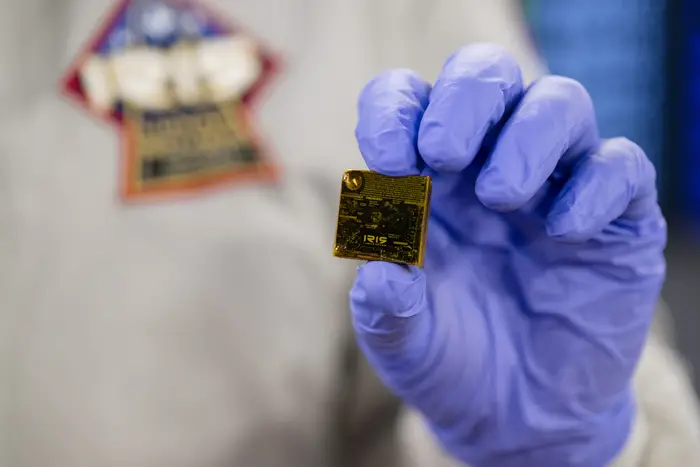

Members of the Iris team have assembled the Iris Lunar Dream Capsule, a tiny payload that will launch aboard Griffin-1, the next lunar lander from Carnegie Mellon spinout Astrobotic. The capsule — smaller than a matchbox — contains the names of team members and supporters, messages and stories, photos, a mini Iris and a bit of the Moonyard from Carnegie Mellon Mission Control.

“Lunar archeologists, maybe 10,000 years from now, could find this and learn about Iris,” said Connor Colombo, the chief engineer on Iris who now works at Astrobotic, adding that understanding English isn’t required, as one of Griffin-1’s other payloads, GLPH(opens in new window), includes an etched version of Long Now's language codec, a modern Rosetta stone. “This will outlast us.”

The original Iris launched on Jan. 8, 2024, from Cape Canaveral, Florida, aboard Astrobotic’s Peregrine lander. However, shortly after the lander separated from the final stage of a ULA Vulcan rocket, a single helium pressure control valve failed, jeopardizing Peregrine’s ability to land safely. Iris would not make it to the moon. Undeterred, the students powered on Iris and started a new mission, communicating with the rover, moving its wheels, checking its systems and proving Iris survived.

“Iris was a successful mission. We proved a student-made mini rover will work in space. Had Iris landed, it would have achieved its objective,” said Zach Muraskin, a recent physics grad who was the science lead during the Iris mission. “Iris, in so many ways, was a symbol of what is possible when space exploration is open to everyone. We’re sending that message to the moon to make a mark that will hopefully outlast humanity.”

The Iris team treated the Iris Lunar Dream Capsule as another mission. The team will leave its mark in two ways. First, Astrobotic offered the team 10 gigabytes of space on Griffin-1. The Iris team will pack its digital space with technical drawings and schematics, photos, videos, messages, names, articles, and more to tell the rover’s story. The digital payload will contain all the information needed to replicate the rover and all the mission data needed to understand what it accomplished.

Second, Colombo purchased a small bit of physical space on Griffin-1 through the MoonBox program, a partnership between Astrobotic and DHL to send mementos to the lunar surface. Colombo reserved a sliver of the 1-inch by 1-inch by 0.25-inch space for a personal message — he proposed to his then-girlfriend, now wife, via a message sent to the moon and back with Iris; she said yes — and gave the rest of the space to Iris.

The team brainstormed how to capture the essence of Iris in a tiny format accessible to whoever or whatever may find it on the moon. The monument had to withstand the harsh lunar environment. It couldn’t rely on technology that may be obsolete or degrade over time.

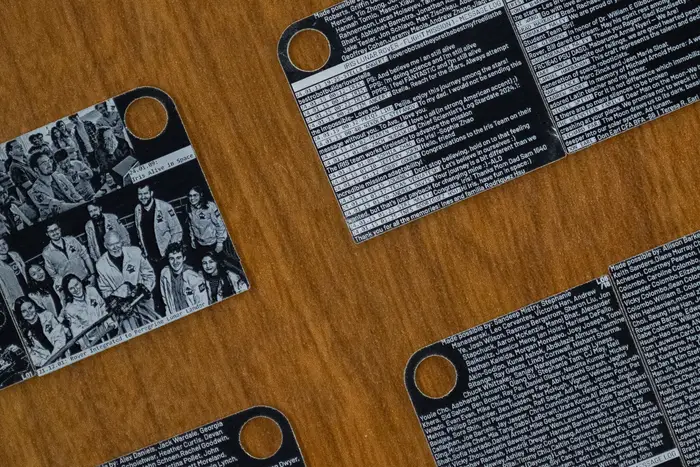

A two-fold solution emerged. Text was etched on both aluminum plaques and a silicon chip. The aluminum plaques contained more than 800 names of Iris team members; messages from Iris team members and donors that flew on Iris during its mission; messages sent to Iris by the team during the mission; additional messages collected for the monument; mechanical drawings of the rover; photos to tell the rover’s story; and a dedication that ends with, “Whoever finds this, we hope you find inspiration in Iris.”

The text on the eight plaques is readable — barely — to the naked eye. The images and drawings are clear.

“This payload helps preserve the legacy of the countless hours of hard work that made Iris a reality,” said Colombo. “We achieved so much during Iris’ journey into space. Now, we get to commemorate that trip and the people who made it possible forever on the moon.”

With redundancy the name of the game in space, the team sought to duplicate this information in another format. HackerFab, a semiconductor fabrication lab in the College of Engineering, nano-engraved the names and messages onto a silicon chip. They included stories marking the Jan. 8, 2024, launch, the contributions to Iris from all seven of Carnegie Mellon’s schools and colleges, and a separate dedication from Muraskin.

“In loving gratitude for the nation, its people, and its values that made this mission possible. May She arrive at safer shores,” it reads, ending with the preamble of the U.S. Constitution.

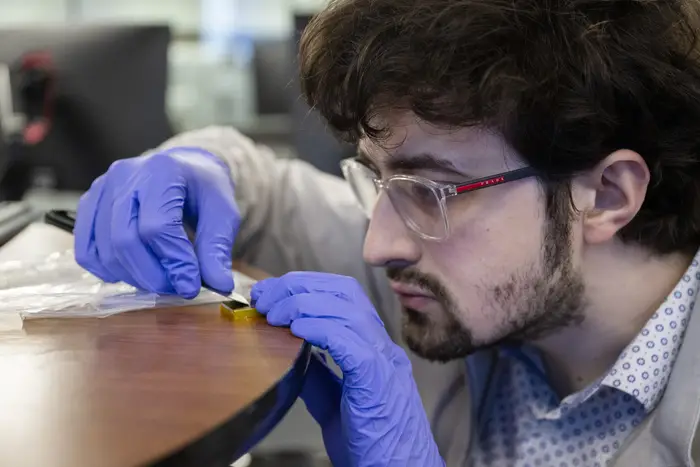

Assembly happened at Carnegie Mellon Mission Control. Members of the team wrapped the aluminum plaques and the silicon chip in Kapton tape. They included a mini Iris, its silhouette smaller than a dime, cut from a spare carbon fiber wheel. At the last moment, they stuck some sand from the MoonYard to the final piece of tape.

Tensions ran high as Colombo used a digital caliper to get the final measurement. A fraction of a fraction of an inch too big could doom the mission. But the payload’s size was perfect, and amidst Colombo’s sigh of relief, a cheer rose up from the team, hands in the air. Mission complete.

Griffin-1 should launch toward the end of 2025. Its destination is the south pole of the moon, the most likely spot to find ice, a source of water and fuel to potentially power future missions deep into space. While the Iris Lunar Dream Capsule will stay put, it is not lost on the team what they were part of.

“We have this opportunity not just to land on the moon, but to participate in the grander dream of humanity expanding into the stars,” Muraskin said. “That’s exciting.”