With StepUp, ETC Students Are Transforming Global Hygiene Education

Media Inquiries

After months of research, development, testing, and a trip halfway around the globe, students from Carnegie Mellon University’s Entertainment Technology Center(opens in new window) have completed a project meant to help children all over the world stay healthy.

The project orginated In 2020, as ETC Assistant Teaching Professor Charles Johnson(opens in new window) gave a virtual talk on the power of design to do good, drawing from his 30 plus years of experience designing footwear for brands such as Adidas and Puma. An attendee put him in touch with the World Shoe Fund(opens in new window), a global humanitarian organization dedicated to distributing shoes to those in need, because they needed help designing a new shoe. Johnson’s talk had made it clear he was the man for the job.

The fund does more than give away shoes. The shoes are part of its larger goal: disrupting the chronic cycle of poverty and disease from the ground up. One example of this is the Wash and Wear program, where World Shoe Fund associates visit schools around the world in order to teach students the importance of proper hygiene, like washing their hands and feet and wearing shoes. Only at the end of the lesson are students given a pair of the shoes Johnson designed.

The World Shoe Fund wanted to push the program further. “You want to be able to not only treat something as it’s happening today, but indefinitely,” said World Shoe Fund President Courtney Cash(opens in new window). “And if their behavior doesn’t change, the same thing is going to keep happening, and we’re not going to have the long-term effect we’re hoping for. What we needed was a way of reinforcing the hygiene lessons we were giving kids.”

"The idea of a game was a simultaneous discovery,” said Johnson, who graduated from CMU's College of Fine Art in 1987. "World Shoe Fund was looking for a way to augment what they do, and I said ‘Well, I’m at the ETC and we create games.’ Those things came together, and it just became very natural.” The World Shoe Fund agreed to sponsor an ETC project.

This fall, the StepUp Project Team(opens in new window) — second-year ETC students Eva Chang, Anna Kim, Lawrence Luo, Regina Xia, Yawen Xiao, and Tyler Yang — came together to make a transformational game, a type of educational game meant to teach players new behaviors or skills. For the StepUp team, the task was to create a game that would be part of the fund’s African initiatives and reinforce hygiene lessons and healthy behaviors long after the initial Wash and Wear school visit ended.

They began by seeking out expert advice on transformational games, and one thing became apparent. “Because we were designing a game for primarily African players, we knew it would be important to make design choices tailored to that context,” Xia said.

The team conducted extensive research on Rwandan culture — one country where the fund plans to pilot the game — through virtual interviews with stakeholders like Rwandan Esports Organization cofounder Jean Christian Kayonga and entrepreneur Peace Fidele Uwihangana.

“We gained a deeper understanding of the environment, lifestyle, public health and gaming culture,” said Xiao. “And we identified the barriers students faced. They don’t understand the risks and consequences, and there’s not enough motivation and reinforcement for them to apply proper hygiene.”

They incorporated what they learned into the development of their game, “Hygiene Hero Cup.” Lessons about cleanliness and the protective function of shoes are woven into the narrative and structure of each of the three minigames; sometimes through function — not wearing shoes slows players down in one minigame — and sometimes through striking visuals. In the second one, for example, the player shrinks down and surfs down an enormous, dirty foot on a bar of soap — encountering harmful elements like germs that are otherwise invisible.

But they knew testing it with their target audience — African students — would be the only way they would know if it worked. The initial plan was to travel to Rwanda halfway through the semester, but an increase in cases of the Marburg virus resulted in the CDC recommending against nonessential travel. The team had to pivot.

After consulting with the World Shoe Fund they set their sights on Ghana, where the fund also has a strong presence. They flew there with a busy itinerary — visits to the World Shoe factory and shoe stores, trips to historic Ghanian sites like Osu Castle, and two days set aside to playtest their game with almost 200 students at local schools.

The team had carefully prepared a lesson plan before leaving, but when they arrived they found themselves having to pivot again. “We quickly realized the scenario was quite different from what we planned,” Yang said. “We found out there would be 30 students in the classroom, all testing the game at the same time — far from our initial idea of small, focused sessions.”

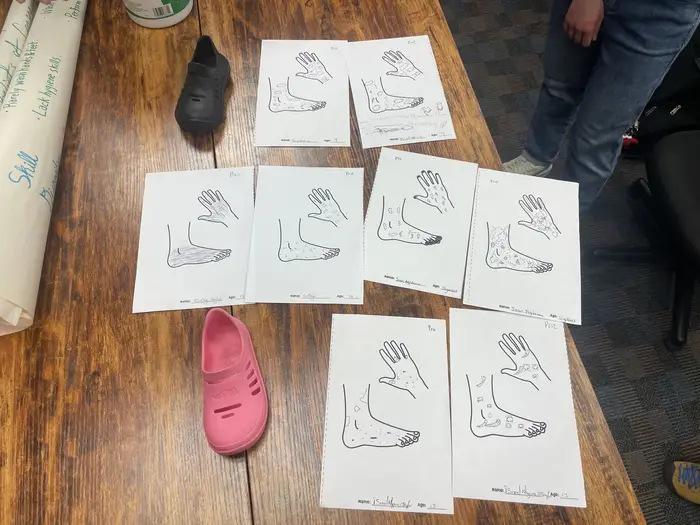

They decided to break the students up into groups and to have them share tablets, which kept all the students — whether watching or playing — engaged with the game. And they made sure that this engagement was captured as data. All the students received pre- and post-session surveys, which included not just questions but also an activity where the students were encouraged to draw what dirty hands and feet looked like.

The first set showed only a basic idea of what dirt is — drawings of hands and feet covered in mud or grime. But after playing the game, the way they students approached the activity changed drastically. They demonstrated a much more thorough understanding of dirt and hygiene, drawing hands and feet crawling with tiny depictions of germs.

“It’s always hard to see how a game teaches a lesson. That takes a long time because it requires research and observation,” Chang said. “But having this worksheet helped us to see if there was an immediate change in their understanding. And we found that afterward we were more sure about the choices we made.”

They headed back to Pittsburgh exhausted, but confident that the game did what they wanted it to do. And after the successful playtests, the fund was equally confident. They’ve already started planning how they can use the game going forward.

“We’re not looking at this in any way, shape, or form as a one-off. This can be applied at scale, and that’s our intent,” Cash said. This is the type of tool we want to see, the kind that utilizes technology to make a game kids want to play that reinforces positive behavior. “This is something we want to take to governments, to ministers of health, and to schools.”

And StepUp isn’t a one-off project for the students that worked on it either, who now see that fun and impact can go hand in hand — an essential part of the ETC ethos. “I wasn’t really interested in the game industry before, because I didn’t feel driven when making a game just for entertainment,” Kim said. “But this semester was different because StepUp was about transforming someone’s behavior and mind. It was more meaningful, and that made the process more fun to me.”