Developmental Psychologists and Statisticians Come Together To Ensure Research Tools Measure Up

Media Inquiries

Developmental psychologists like Catarina Vales want to know how kids understand the world.

Like all researchers, she relies on tools designed to assess how children learn. Though those tests and tasks are considered tried and true, Vales wants to make sure the tools researchers use measure up.

“If you have a ruler that always gives you the same number, but the number is off by 5 inches, your measurement is always going to be wrong,” Vales explained. “Or if your ruler seems to give you a different number each time you use it, that’s another problem. We want to know if our measurements are both correct and reliable.”

Vales is special faculty in CMU’s Department of Psychology(opens in new window). She worked with colleagues Zach Branson(opens in new window) and Anna Fisher(opens in new window) to find a way to test a spatial arrangement task where children organize items in space based on their meanings. The results were published in a methodological article in the journal Infant and Child Development(opens in new window).

The spatial arrangement task can help researchers understand how connections are formed in the brain while children are learning to understand the world. For example, Vales said that when adults hear the word “cat,” many of them will think of the word “dog” because there is a strong association between those two concepts — they are both animals, mammals and pets and are found together in several English expressions, such as “it’s raining cats and dogs.”

Understanding semantic knowledge, the way people organize words by meaning, can help researchers understand crucial parts of child development, like how children learn to read.

“We know that one of the basic cognitive processes that supports the ability to read is the ability to make predictions about what's going to come next in the text. So if you're a kid who has a little bit of knowledge about mammals, if you read the word ‘mammal’ you can start to constrain the things that that paragraph is going to be about,” Vales said.

What is the spatial arrangement task?

The spatial arrangement task has been used extensively with both adults and children. For the paper, the researchers used data from five previous studies that used it to test semantic knowledge.

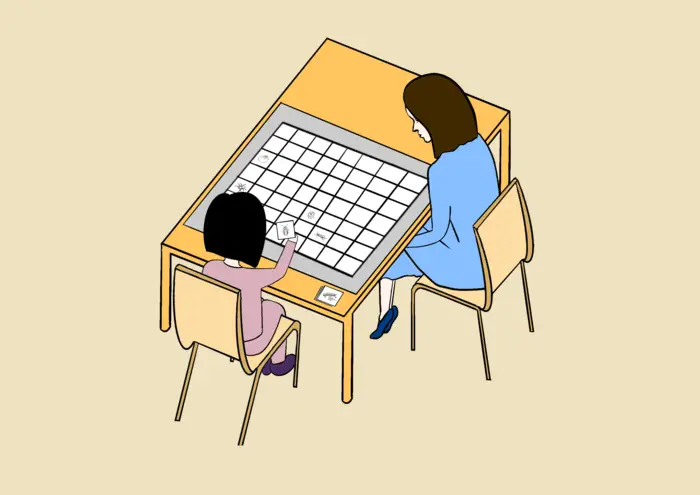

In the task, children are asked to arrange pictures that depict concepts of interest on a board, placing similar things together. The words are in multiple categories. For example, in one such task children would be asked to arrange tiles picturing mammals, birds and reptiles by placing like items together on the board.

Once a child organizes their word tiles on the board, researchers take a picture of it and calculate the distances between all of the items on the board. If the child has a good understanding of the difference between categories, the tiles should be in separate clusters. A child with well-differentiated knowledge of animals would cluster mammals together, birds together, and reptiles together.

Nontraditional data thrills statistician

The researchers looked at three things in the data from previous studies that used the spatial arrangement task — construct validity (whether the test measures what it is supposed to), internal consistency (whether kids get similar results with slightly different questions) and test-retest reliability (if kids get similar results on different days). That generated a lot of data, Vales said.

“We needed to calculate a single score that could summarize a child's performance and a way to compare across the time points or across different versions of the task,” she explained.

That’s where Branson came in.

Branson, an assistant teaching professor in the Department of Statistics & Data Science(opens in new window), worked with Vales and Fisher to find a way to score the way the children placed the tiles on the board. He said that it was exciting to work on a different type of dataset.

“In a traditional dataset, each subject is just a row on a spreadsheet. But here each subject is the image of the board that the kid created,” Branson explained. “We needed to numerically summarize what these boards represent.”

If the children created a board with distinct categories, clearly demonstrating that they had a good understanding of those concepts, the board should get a higher score. Branson explained that it is important to understand not only how children make connections within categories, but also how they make connections between categories.

“If a kid arranges a bunch of bird tiles in one area of the board, they are creating a cluster or grouping of tiles. 'Clusters' is a special word in statistics, and when Catarina explained this project, bells started ringing in my head,” Brason explained. “I thought we could use traditional clustering techniques to analyze this nontraditional data. From there, we could think about how homogeneous the clusters were, and how separated they were on the board, to create a single score.”

Branson noted that the researchers also were able to compare those scores to what they would expect to see if children randomly arranged the tiles on the board.

Spatial arrangement task passes the test

The good news: Researchers found that the spatial arrangement task, at least when used to test semantic knowledge, is a valid task, Vales said.

She explained that it’s especially important to do this kind of work in developmental psychology, because collecting data from children is often expensive and time intensive, and can generate “noisy data.”

“With kids we often are constrained by how many trials we can test them on, and sometimes they're going to be distracted, or they just want to be done and they don't know how to tell that to the adult that is asking them to do the task,” she explained. “But if you're gonna spend all this time and resources, you should really make sure that the tasks you're using are good for the purpose that you want to use them for.”

Branson said he expects to do more work scoring nontraditional data, such as text, images or other things that are hard to quantify.

“This is where the field of statistics and data science is going. I've been dipping my toe into more and more, I guess. Now I've dipped my foot at this point,” he said.