CMU AI Tools, Including a Chatbot for Controversial Topics, Connect Humanities and Social Sciences to Innovation

Media Inquiries

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University are working to develop tools to incorporate artificial intelligence into the humanities and social sciences. In the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences(opens in new window), several initiatives and projects are underway to harness the power of AI.

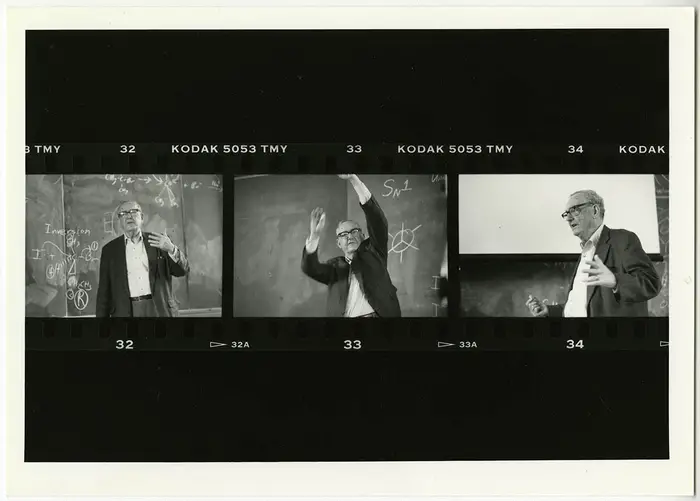

Richard Scheines(opens in new window), the Bess Family Dean of the Mariana Brown Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences, compared the hesitation to embrace AI in education to those 60 years ago unwilling to adopt usage of the calculator (“no one will be able to add or subtract!”), which is now a standard feature on six billion cellphones throughout the planet.

“AI is, and should be, changing the way we need to educate our students,” he said. “Employers are going to expect our students to be able to use these tools. So resisting the use of AI in education is pointless — and I’d rather see our faculty embrace it and innovate with it rather than resist it and hold it at bay.”

Leaders at Dietrich College understand that teaching and research tools harnessing the latest AI technology are a perfect fit for the university, with its history of innovation in AI dating back to the 1950s(opens in new window), according to Vincent Sha(opens in new window), associate dean of IT and operations for Dietrich College, and technical lead for the Open Forum for AI(opens in new window) (OFAI). The pioneering work of Herb Simon, who held an appointment in Dietrich College, laid the foundation for the fields of AI and cognitive science.

“We must ask ourselves, ‘How can we as humanists and social scientists be embracing this legacy?’” Sha said.

Along with Joel Smith(opens in new window), former CMU vice provost for Computing Services and chief information officer, now Distinguished Career Teaching Professor in the Department of Philosophy(opens in new window), Sha co-led a college-wide faculty committee that developed a guide for AI best practices in the classroom and seeded ideas for generative AI teaching interventions.

In addition, Sha and the Dietrich College Computing and Operations team have explored new innovations in artificial intelligence through projects such as:

- Creating the Dietrich Analysis Research Education ecosystem, a collection of tools designed to ease AI adoption by reducing logistical and technological barriers to access. The ecosystem leverages existing and emerging capabilities of large language models such as OpenAI and Claude to enhance administrative, education and research productivity as well as manage costs and deployment. Tools will be released as open-source AI, further democratizing access to advanced AI capabilities in academic settings.

- Collaborating with Rafael López(opens in new window), deputy director of the Carnegie Mellon Institute for Strategy & Technology(opens in new window) (CMIST), they co-sponsored a student internship program focused on the development of LLM-powered applications, including the Operational Gaming Environment (OGE). In this environment, players interact with a central white box system and collaborate with four LLM-based advisors: diplomatic, military, economic and intelligence. Simulations, which will be piloted in classrooms next year, will serve as a testbed for exploring team-building dynamics, analytical reasoning and the potential of AI-assisted decision-making in high-stakes environments.

- Working with Social and Decision Sciences Professor Daniel Oppenheimer(opens in new window) on Socratic textbooks. These AI-powered books deliver personalized content and tutoring through conversational interactions while adapting to each student's pace and interests using the Socratic method. This new approach provides instructors with detailed insights on individual and class-wide learning progress, enabling targeted interventions and curriculum adjustments.

- Facilitating professional development for faculty, staff and students. These include working with Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation to support the Generative AI Teaching as Research (GAITAR) Initiative(opens in new window), which is meant to measure the impacts of the generative AI tools on CMU students’ learning and educational experiences. In addition, Sha has offered a three-part series for first-time faculty on AI tools that can aid their teaching and research.

“How can we scaffold the interactions with generative AI, focusing on offloading lower-order thinking tasks and interfere with the acquisition of higher-order thinking, so that we enhance, and not inhibit, human intelligence and growth?” Sha said.

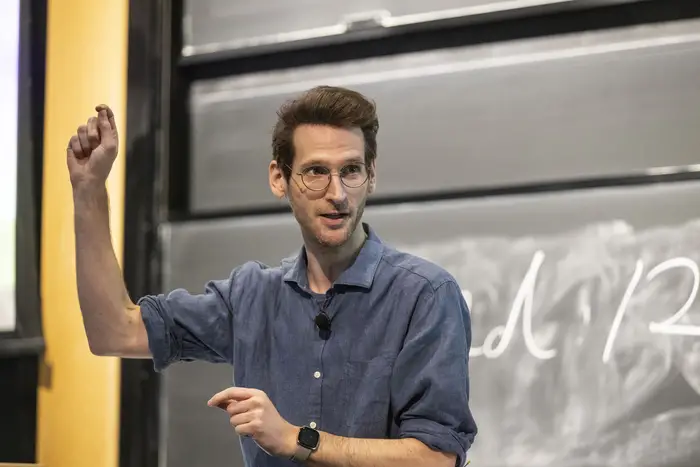

Initiated by Simon Cullen(opens in new window), assistant teaching professor in the Department of Philosophy, one additional Dietrich College project is meant to develop methods to help people reason better and resolve disagreements.

AI chatbot inspired by ancient Greek philosopher spurs more robust debate

Cullen taught Dangerous Ideas in Science and Society, a course that asked students to analyze arguments around tough topics.

“Underlying the work we’ve done on polarization and on reasoning is this basic idea that we really have underestimated what human rationality is capable of,” he said. “Often what’s driving some of our biases is difficulty of reasoning and communication, especially when you’re talking to someone you disagree with about many fundamental assumptions.”

Motivated by his own personal interest in AI, Cullen fine-tuned a large language model to synthesize tens of thousands of words of students’ feedback from his class. He used this in order to create a student he could interact with and talk to in a naturalistic way to better understand how real students experienced his class. With the help of Sha, this became Robocrates, a chatbot to help students practice arguing about controversial topics in a “safe” environment.

Now, he’s working on Sway, an AI-scaffolded student chat platform that facilitates productive discussions between students on controversial topics.

“Sway uses AI to help people communicate better, understand each other better and potentially hate each other less,” said Nicholas DiBella, postdoctoral research fellow in the Department of Philosophy(opens in new window).

Previously, DiBella worked on research about visualizing the flow of arguments and how people reason about uncertainties and probability — until OpenAI released GPT-4 for ChatGPT in March 2023.

“We realized just how awesome it would be at helping people reason better, communicate better, potentially resolve arguments, or, more generally, help people understand each other better, especially when they disagree about heated topics,” DiBella said.

If AI can help someone reason more clearly and effectively, then they can more easily bridge the gap between them and whoever they are talking to, Cullen said. The more two people disagree with each other, the more they make and rely on assumptions instead of reason.

“People tend to rely on shortcuts and rules-of-thumb summaries that they create in their heads while they’re listening to their opponents,” Cullen said. “Those summaries can be outrageously biased."

Applying AI to guide difficult conversations

Cullen recognized that educational researchers have known for more than 40 years that one-on-one human tutoring is the gold standard. However, AI-driven computer tutors that provide individualized feedback can come close to that.

In the 1980s, CMU researchers John R. Anderson(opens in new window), Ken Koedeinger(opens in new window) and Albert Corbett(opens in new window) began to develop Cognitive Tutors for algebra and other subjects, and this technology has been so effective that it is now used by more than a half-million students per year. Vincent Aleven(opens in new window), a professor in the Human-Computer Interaction Institute(opens in new window), has applied AI to legal reasoning.

But before Robocrates, AI had never been applied to difficult conversations in a classroom setting at CMU.

Even in an academic setting, students aren’t always comfortable participating in debates, but doing so is the best way to foster better understanding, Cullen said.

“The topics discussed in my class can be really controversial and students are sometimes afraid to speak freely about them because of cancel culture,” he said. “Our thought was: ‘Wouldn’t it be terrific if we could create a bot that would allow them to argue about whatever difficult topic was holding them back.’ ”

Cullen collected data from the students who used Robocrates during the fall of 2023, and the feedback was overwhelmingly positive. The students were required to interact with the bot for 20 minutes, but some logged 40- to 50-minute sessions.

Then, the researchers wanted to take the application of artificial intelligence a step further.

“We took the lessons we learned from Robotcrates and really started asking ourselves, ‘in today’s landscape, how can we use AI to help for social good?’ ” Sha said.

With Sway, AI guides people toward a civil argument

Now, using conversations facilitated by Sway, the research team is gathering data to gain insights into communication and depolarization.

Faculty from more than 50 institutions — including Harvard, UCLA, Michigan and Vassar — have signed up to use Sway with their students. Many students volunteer as participants in Cullen and DiBella’s research, allowing them to test the platform and collect data to fuel further improvements.

“The goal of our research with Sway is to create environments where the most polarizing topics can be discussed and debated on campus but with guardrails that promote understanding and rationality rather than hostility and even more polarization,” says DiBella’s voice in a demo video for Sway.

Cullen said Guide — Sway’s AI facilitator — is “agential” in that it proactively engages without students needing to summon it, instead of the bot serving as an assistant.

“Guide is always monitoring the chat in the background. Our goal is for it to make intelligent decisions about how to guide that discussion, how to encourage the participants to uncover areas of common ground, or at least to clarify their disagreements,” he said.

Sway has two levels of AI intervention. First, it will give suggestions if someone’s written reply includes unconstructive language, such as name-calling or loaded words and phrases.

“Guide is very good at identifying situations like that and helping people get on the same page and actually listen to each other,” Cullen said. “Guide will step in and try to defuse and de-escalate the situation.”

It even recognizes emojis and suggests new responses that match the way the human conversation partners use capitalization.

Sway is programmed to flag messages that include insults or emotionally charged words, but still make a point, and it suggests a new way to phrase the text into something more constructive. Then, the human interacting with it can either accept that rephrasing, refresh it for another suggestion, or reject it and rewrite the whole message.

“Guide is there if users have questions about factual information, whether it’s about science or maybe the history of a certain topic, or perhaps one user might just say something that is blatantly and uncontroversially incorrect,” he said. “Guide will step in and correct them.”

Learn more about AI at Dietrich College

The Dietrich College is shaping artificial intelligence through the humanities and social sciences.